Celiac Disease Definitions

Where Do These Celiac Disease Definitions Come From?

The “Oslo definitions” provided on this page refer to celiac disease definitions and related definitions upon which consensus was reached among an international, multi-disciplinary task force of physicians.

The one in-person meeting of this task force (among other methods of communication) was held in Oslo, Norway, at the 14th International Celiac Disease Symposium in June 2011, hence, the use of “Oslo” in “Oslo definitions.”

This task force consisted of 16 physicians from 7 countries (Argentina, Finland, Italy, Norway, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States). Their medical specialties included gastroenterology, histopathology, pediatrics, neurology, and dermatology.

The task force was split into small teams that performed literature reviews on 1–4 terms and devised suggested celiac disease definitions as well as definitions for related terms. In total, the task force evaluated over 300 papers found through PubMed literature searches. All members of the task force participated in a web survey and discussions that led to a consensus for these definitions.

In January 2013, this task force published the results of their work in an article titled The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms in the journal Gut.

Note that “coeliac” is the perfectly legitimate British spelling of “celiac.” For the purpose of consistency on CeliacFAQ.com, I use “celiac” here and elsewhere.

Definition of “Gluten-Related Disorders”

“Gluten-related disorders” is an umbrella term used to describe all health conditions related to gluten. These disorders include celiac disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, gluten ataxia, and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

The task force prefers the term “gluten-related disorders” over the term “gluten intolerance.” For an explanation, see Terms Whose Use Is Discouraged.

Celiac Disease Definitions Developed by the Task Force

The task force defined the following terms related specifically to celiac disease. Some of these celiac disease definitions have been slightly modified to fit the structure and style of my article. I include commentary to expound on some aspect of each definition.

Celiac Disease Definition

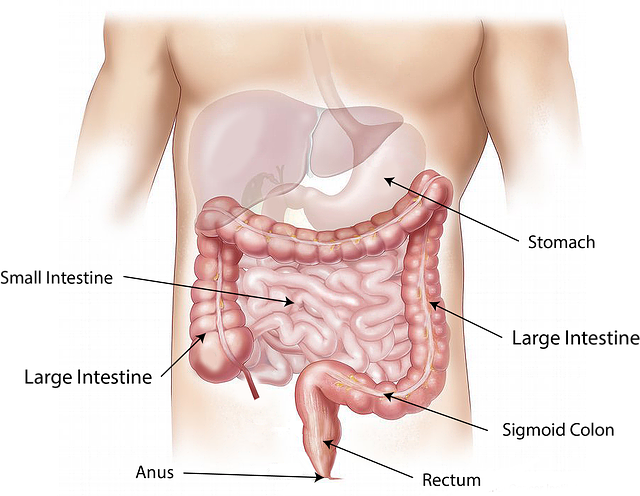

Celiac disease is “a chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals.”

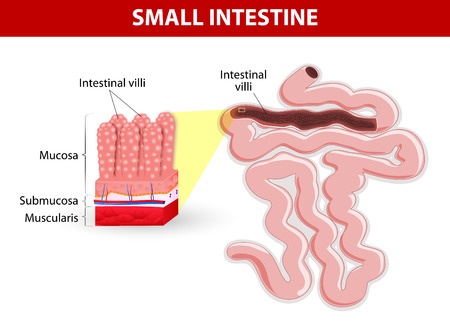

Commentary: The term “enteropathy” refers to any pathology specific to the small intestine. In biopsy-confirmed celiac disease, the intestinal villi are found to be damaged. The term for this damage is “villous atrophy.”

Equivalent terms historically used for celiac disease include: sprue, coeliac sprue, gluten-sensitive enteropathy, and gluten intolerance. The task force discourages the use of these terms.

I find it curious that this definition of celiac disease doesn't identify the disease as autoimmune in nature. The term “immune-mediated” is not synonymous with “autoimmune.” Celiac disease is not the only immune-mediated enteropathy—so is autoimmune enteropathy.

Classical Celiac Disease Definition

Classical celiac disease is a form of celiac disease that “presents with signs and symptoms of malabsorption. Diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, or growth failure is required.”

Commentary: The term “steatorrhea” refers to the excretion of increased quantities of fat in the stool due to reduced fat absorption by the intestines.

Classical celiac disease is less common than non-classical celiac disease. However, toddlers and young children tend to exhibit the more classic signs and symptoms of celiac disease. As with adults, older children tend to exhibit non-classical symptoms of the disease.

The classical symptoms in younger children tend to commence between 9–24 months of age. Symptoms begin at some point after gluten-containing foods are introduced in their diet. (1)

Non-Classical Celiac Disease Definition

Non-classical celiac disease is a form of celiac disease that presents “without signs and symptoms of malabsorption.”

Commentary: Common symptoms of non-classical celiac disease include digestive symptoms other than diarrhea as well as extraintestinal symptoms (which are experienced outside of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract).

Digestive symptoms other than diarrhea include canker sores, acid reflux or the more serious gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), bloating, vomiting, constipation, and dyspepsia (indigestion).

Extraintestinal manifestations include osteopenia/osteoporosis, anemia, cryptogenic hypertransaminasemia (elevation of a certain group of liver enzymes), and recurrent miscarriages. (2)

In fact, the most common presentation of non-classical celiac disease (and possibly the only finding) is iron-deficiency anemia. (3)

Asymptomatic Celiac Disease Definition

Asymptomatic celiac disease is a form of celiac disease that is “not accompanied by symptoms even in response to direct questioning at initial diagnosis.”

Commentary: The term “asymptomatic celiac disease” is synonymous with the commonly used term “silent celiac disease.” However, use of the latter term is discouraged.

People with asymptomatic celiac disease have no symptoms that respond to a gluten-free diet.

Despite having no symptoms related to celiac disease, they meet all the other criteria for a celiac disease diagnosis, including having small intestinal damage consistent with the disease.

These patients are typically identified during routine screening, which is performed because they have a family member diagnosed with celiac disease.

Symptomatic Celiac Disease Definition

Symptomatic celiac disease is “characterized by clinically evident gastrointestinal and/or extraintestinal symptoms attributable to gluten intake.”

Commentary: The term “symptomatic celiac disease” replaces the term “overt celiac disease.”

For a long list of possible symptoms of celiac disease, see What Are Celiac Disease Signs and Symptoms?.

Potential Celiac Disease Definition

Potential celiac disease describes “people with a normal small intestinal mucosa who are at increased risk of developing celiac disease as indicated by positive celiac disease serology.”

Commentary: The immune systems of people with potential celiac disease are producing celiac disease autoantibodies. These autoantibodies show that the immune system is attacking the body's small intestine. Alessio Fasano, MD, recommends that people with potential celiac disease consume a gluten-free diet to treat symptoms (if they are present) and to prevent late-onset complications. (4)

Refractory Celiac Disease Definition

Refractory celiac disease (RCD) consists of “persistent or recurrent malabsorptive symptoms and signs with villous atrophy despite a strict gluten-free diet for more than 12 months.”

Commentary: According to a 2010 article in the journal Gut, the prevalence of this form of celiac disease is unknown but probably rare. Two types of this disease have been identified: RCD type 1 and RCD type 2. The prognosis of RCD type 1 is much better than for RCD type 2.

Symptoms of refractory celiac disease are often severe and require therapeutic interventions beyond strict adherence to the gluten-free diet. For example, treatment with steroids such as prednisone or budesonide can induce clinical remission and mucosal recovery in people with RCD type 1.

Unfortunately, despite steroid treatment, people with RCD type 2 have a poor prognosis with 5-year survival rates of 40–58%. The poor prognosis is largely explained by the significantly more frequent progression to enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. (5)

Subclinical Celiac Disease Definition

Subclinical celiac disease is a form of celiac disease “that is below the threshold of clinical detection.”

Commentary: To clarify, people with subclinical celiac disease do not express signs or symptoms that are sufficient for prompting celiac disease testing in routine clinical practice.

“Genetically at Risk of Celiac Disease” Definition

Genetically at risk of celiac disease refers to “family members of celiac disease patients who test positive for HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8.”

Most people who are genetically at risk for celiac disease never develop it.

For information about celiac disease genetics, see Is Celiac Disease Genetic? and What Is the Celiac Gene?.

Definitions for Other Gluten-Related Disorders

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Definition

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity refers to “one or more of a variety of immunological, morphological, or symptomatic manifestations that are precipitated by the ingestion of gluten in individuals in whom celiac disease has been excluded.”

Commentary: Upon first usage of “non-celiac gluten sensitivity,” the term is often shortened to “gluten sensitivity” or abbreviated to “NCGS.” The task force uses NCGS in its paper, but not the shortened form of the term (gluten sensitivity).

According to Alessio Fasano, MD, “Although symptoms (particularly gastrointestinal) are often similar to those of celiac disease, the overall clinical picture [of non-celiac gluten sensitivity] is less severe.” He reported that research at the University of Maryland Center for Celiac Research showed that “gluten sensitivity is a different clinical entity that does not result in the intestinal inflammation that leads to a flattening of the villi of the small intestine that characterizes celiac disease.” (6)

Nor does gluten sensitivity generate tissue transglutaminase (tTG) autoantibodies, which are used to diagnose celiac disease. For these reasons and more, researchers believe that gluten sensitivity does not cause the long-term intestinal damage that can result in untreated celiac disease.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis Definition

Dermatitis herpetiformis is “a cutaneous manifestation of small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten. It is characterized by herpetiform clusters of pruritic urticated papules and vesicles on the skin, especially on the elbows, buttocks, and knees, and IgA deposits in the dermal papillae.”

Commentary: “Herpetiform clusters of pruritic urticated papules and vesicles on the skin” refers to blistering skin lesions that resemble herpes lesions. However, dermatitis herpetiformis is not related to or caused by any herpes virus.

Essentially, dermatitis herpetiformis is a skin manifestation of celiac disease. As with celiac disease, dermatitis herpetiformis responds to a gluten-free diet.

Gluten Ataxia Definition

Gluten ataxia is an “idiopathic sporadic ataxia [with] positive serum antigliadin antibodies even in the absence of duodenal enteropathy.”

Commentary: Gluten ataxia is one of the neurological manifestations attributed to celiac disease. “Ataxia” refers to the loss of balance and coordination of complex movements such as walking, speaking, and swallowing. The damage occurs to a part of the brain called the cerebellum.

Terms Whose Use Is Discouraged by the Task Force

In addition to providing celiac disease definitions for preferred terms, the task force listed terms whose use they discourage, along with some discussion of each “deprecated” term.

- Atypical celiac disease – Historically, this term has had multiple meanings and can only be used in the context of typical celiac disease (a term that researchers don't recommend using). Some patients previously described as having atypical celiac disease might fit into the category of non-classical celiac disease.

- Celiac disease serology – Ideally, specify the antibody tests used instead of using this generic term. (Interestingly, researchers use this term in their definition of potential celiac disease!)

- Gluten intolerance – Researchers believe this term is “non specific and carries inherent weaknesses and contradictions.” For example, the term has been used as a synonym for celiac disease as well as to indicate that a patient experiences improvement after starting a gluten-free diet (even though the patient doesn't have celiac disease). In addition, gluten intolerance might actually be the result of problems with wheat components other than gluten.

Instead, use the term “gluten-related disorders” as the umbrella term for disorders caused by gluten exposure. - Gluten sensitivity – This term has been used inconsistently with different meanings. For example, some research papers use the term as a synonym for celiac disease. Other papers use it as the umbrella term for all gluten-related disorders. Other papers have even other purposes for this term. Therefore, researchers discourage the use of this term.

Instead, use “celiac disease” where it applies. Use “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” where it applies.

I still see gluten sensitivity used in all different contexts. In my editorial opinion, it's fine to use “gluten sensitivity” when it applies to non-celiac gluten sensitivity. However, the longer version should be used at least at the first reference with the shortened version following in parentheses. For example: non-celiac gluten sensitivity (gluten sensitivity). - Latent celiac disease – The medical literature reveals at least five different definitions of latent celiac disease. However, the term is most often used interchangeably with potential celiac disease. Instead, use the latter term.

- Overt celiac disease – Instead, use symptomatic celiac disease. The two terms aren't quite synonymous.

- Silent celiac disease – Instead, use asymptomatic celiac disease (though the terms are synonymous).

- Typical celiac disease – Historically, this term has been used to describe the form of celiac disease that presents with malabsorption signs and symptoms. However, as the researchers note, the clinical presentation of celiac disease has changed over time, and the term “typical” suggests that this form of celiac disease is the most common. That is untrue, so researchers discourage the use of this term.

If appropriate, use the term “classical celiac disease.”

References

1. Guandalini S. Pediatric Celiac Disease Clinical Presentation. Medscape. Updated: Nov 18, 2014. [Article]

2. Volta U, Caio G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R. The changing clinical profile of celiac disease: a 15-year experience (1998–2012) in an Italian referral center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;(14):194 [PDF]

3. Snyder CL, Young DO, Green PHR, et al. Celiac disease. 2008 Jul 3. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2015. [Full text]

4. Fasano, A. A biopsy should not be required to make the diagnosis. American Gastroenterological Association web site. Oct 1, 2013.

5. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray, JA. Classification and management of refractory celiac disease. Gut. 2010;59(4):547-557. [PDF]

6. Veltman E. Interview w/ Dr. Alessio Fasano Part 3: Gluten Sensitivity (A New “Food Allergy”). The Tender Foodie Blog. Jan 3, 2012. [Article]

CeliacFAQ.com home page > Celiac Disease FAQ > Celiac Disease Definitions