What Celiac Disease Testing Is Required

to Confirm a Diagnosis?

Regarding celiac disease testing: According to a 2013 article in BMC Gastroenterology, no single test can conclusively diagnose or exclude celiac disease in every individual. (1)

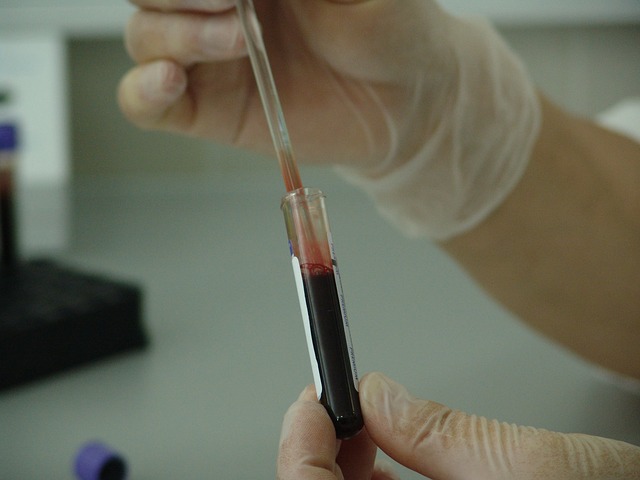

Celiac disease testing begins with blood tests that measure the amount of certain antibodies in the blood. If this initial testing yields results that are inconclusive or suggestive of celiac disease, then many doctors order a small intestinal biopsy to either confirm or rule out the disease.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association and the American College of Gastroenterology, the small intestinal biopsy remains the “gold standard” for celiac disease diagnosis. (2,3)

However, according to celiac disease researcher and pediatric gastroenterologist Alessio Fasano, MD, “We don't call the biopsy the 'gold standard' anymore. In fact, it is not the silver standard, nor even the copper standard! One main reason is that someone with celiac disease may have no damage to the small intestine. Not yet.” (4)

In fact, a debate about whether the intestinal biopsy is always necessary is ongoing.

Note that some people refer to the procedure for the intestinal biopsy as the “celiac disease endoscopy.“

Celiac disease testing must be performed before you eliminate gluten from your diet. Positive blood tests and findings from a small intestinal biopsy might improve on a gluten-free diet. Thus, the test results could be falsely negative when, in fact, you do have celiac disease.

I went gluten free before undergoing celiac disease testing. I didn't know that I should be tested for this disease and evidently, neither did the two doctors I was seeing at the time. But I have since discovered that I have the highest risk genetics for celiac disease.

It's best to know where you fall on the spectrum of gluten-related disorders. Don't make the same mistake I did.

Is There a Single Blood Test for Celiac Screening?

Sometimes, as a first step, doctors order only a single screening blood test for celiac disease. This test, called the anti-tissue transglutaminase (anti-tTG) antibody, IgA, test, is commonly abbreviated as tTG-IgA.

Running this test alone is especially useful for screening at-risk populations, such as family members of people diagnosed with celiac disease.

If this celiac screening test yields a positive result, further steps must be taken to either diagnose or rule out celiac disease.

For more information, see What Is the Best Screening Blood Test for Celiac Disease?.

What Is the Celiac Disease Panel?

Among patients with disease, a test's “sensitivity” refers to the probability of a positive result. Conversely, among patient's without disease, a test's “specificity” refers to the probability of a negative result.

For example, according to the Celiac Disease Foundation, the tTG-IgA antibody test will be positive in about 98% of people with celiac disease who eat gluten. This test will be negative in about 95% of people without celiac disease.

Thus, out of 100 patients with celiac disease, 98 of them will receive a positive tTG-IgA test result. Conversely, out of 100 patients without celiac disease, 95 of them will receive a negative tTG-IgA test result.

For celiac disease testing, doctors typically order a group of blood tests called the celiac disease panel, or simply, the celiac panel. Which tests are included in this panel vary by the lab or by the doctor.

The following tests are commonly performed as part of a celiac panel:

- Anti-tTG antibodies, IgA – Also known as tTG-IgA, this is the most common test used for celiac screening purposes. It is the most sensitive blood test for celiac disease. It can also be used to monitor people with celiac disease after they begin a gluten-free diet.

- Deaminated gliadin peptide antibodies (DGP IgA and IgG) – This test might be positive in people with celiac disease who receive a negative result for the tTG-IgA test, especially in children under the age of 2. This test can also be used to monitor people with celiac disease.

- Anti-endomysial antibodies, IgA (EMA-IgA) – This test is highly specific to celiac disease. A person with elevated EMA-IgA antibodies has a nearly 100% chance of having celiac disease.

However, according to the University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center, with this test, as many as 5–10% of celiacs receive a false negative result, so it is less sensitive than the tTG-IgA test. (5) In addition, the EMA-IgA test is subject to added cost and interpretation error, so it is used less often.

If the results of the celiac disease panel warrant further investigation of the possibility of a celiac disease diagnosis, then many doctors will order a small intestinal biopsy.

It is rare for people with celiac disease to have negative celiac antibody tests. However, if symptoms persist and celiac disease is still suspected, then a small intestinal biopsy might be warranted.

Other Blood Tests Related to Celiac Disease Testing

- Total Serum IgA – This blood test checks for an IgA deficiency. About 2–3% of people with celiac disease have an IgA deficiency. As a consequence, they can receive false negative results from the celiac panel.

For people with an IgA deficiency, instead of being tested for the IgA class of antibodies, they should be tested using the IgG class of antibodies. For example, the tTG-IgG test can be ordered instead of the more common tTG-IgA test. - In the past, the anti-gliadin antibody (AGA-IgA or AGA-IgG) test was used for celiac disease testing. Due to concerns with its accuracy, the American Gastroenterological Association and the American College of Gastroenterology no longer recommend this test.

- Genetic testing for celiac disease – This testing does not require a gluten-containing diet because it is not checking for the presence of antibodies. Instead, it checks for the presence of the celiac gene (HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8).

People with neither gene can be fairly confidant that they will never develop celiac disease. However, according to Dr. Fasano in his book Gluten Freedom, 2–3% of people with celiac disease don't have either celiac gene.

For more information about celiac disease genetics, see What Is the Celiac Gene?.

Celiac Disease Testing: The Small Intestinal Biopsy (Also Known as the “Celiac Disease Endoscopy”)

Many doctors consider the small intestinal biopsy the “gold standard” for diagnosing celiac disease. For them, celiac disease testing isn't complete until this step is taken.

If a patient has one or more positive blood tests (also referred to as “positive serology”) for celiac disease, his or her doctor typically orders a more invasive procedure called an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

A gastroenterologist performs an upper GI endoscopy to biopsy, or take small samples of, the upper small intestine (called the duodenum) while the patient is sedated or unconscious from anesthesia. The gastroenterologist uses an instrument called an endoscope to perform this procedure.

An endoscope is a long, thin tube with a video camera and light on the end. By adjusting the endoscope's controls, a gastroenterologist can guide the flexible instrument through the patient's upper digestive system in order to examine its inside lining. The upper digestive system includes the esophagus, the stomach, and the duodenum.

The American College of Gastroenterology recommends multiple biopsies of the duodenum, including one or two biopsies of the duodenal bulb (the part closest to the stomach; it's about 5 centimeters long) and at least four biopsies of the duodenum beyond that area.

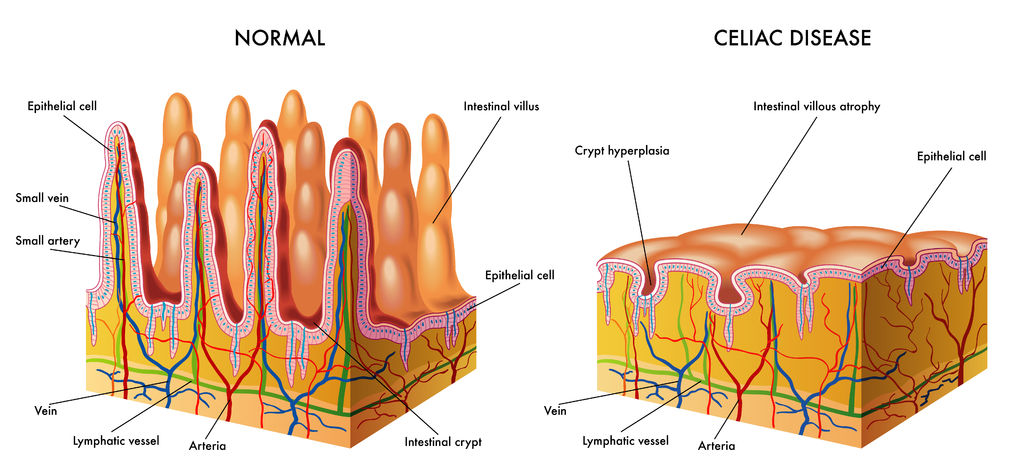

The biopsy samples are then sent to a pathologist who examines them under a microscope to check for histological (tissue structure) changes that are characteristic of celiac disease.

Specifically, the pathologist is looking for villous atrophy. “Villous atrophy” refers to the erosion of the tiny finger-like projections in the intestines called “villi.” These villi help you absorb nutrients.

If villous atrophy is found, the patient is diagnosed with celiac disease and placed on a gluten-free diet.

If the biopsy results are negative, it is typically assumed that the patient does not have celiac disease.

However, I recall Peter Osborne, DC, founder of the Gluten Free Society, mentioning a patient who came to him for help after she finally received a positive biopsy result for celiac disease from her ninth small intestinal biopsy. All previous biopsies were negative.

The Small Intestinal Biopsy for Celiac Disease Is Not a Perfect Diagnostic Tool

The small intestinal biopsy (sometimes referred to as the “celiac disease endoscopy.”) is not without pitfalls. The following are some of the reasons:

- According to Italian researchers Giacomo Caio and Umberto Volta, “it is well known that clinical and serological features of [celiac disease] can precede histological changes by up to 2 years.” (6)

- Celiac disease lesions in the small intestine can be patchy, and the biopsies for celiac disease testing might miss them entirely.

- In some people, deterioration of the small intestinal villi occurs in the middle part of the small intestine, called the jejunum. The jejunum is not accessible during an upper GI endoscopy.

- Conditions other than celiac disease can cause villous atrophy. They include small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), Crohn's disease, food allergy, and infectious enteritis (such as a parasitic infection called giardiasis).

Also see Is the intestinal biopsy always necessary? for differing views about this matter.

References

1. Bürgin-Wolff A, Mauro B, Faruk H. Intestinal biopsy is not always required to diagnose celiac disease: a retrospective analysis of combined antibody tests. BMC Gastroenterology. 2013;13:19. [Full Text]

2. Kagnoff MF. AGA Institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Dec 10, 2006. [Guidelines]

3. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA. Diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676. [Guidelines]

4. Veltman E. Dr. Fasano on new gut & autoimmune research, autism, & clearing up the gluten confusion with his new book. The Tender Foodie Blog. May 1, 2014. [Article]

5. Antibody blood tests. The University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center. [Article]

6. Caio G, Volta U. Coeliac disease: changing diagnostic criteria?. Gastroenterol Hepatol From Bed to Bench. 2012;5(3):119-122. [Full Text]

CeliacFAQ.com home page > Celiac Disease FAQ > What Celiac Disease Testing Is Required to Confirm a Diagnosis?