Is the Intestinal Biopsy for Diagnosing Celiac Disease

Always Necessary?

Receive a free 50+ page guide with gut rebuilding recipes and tips from 45 wellness experts, courtesy of gut health expert Summer Bock. Also check out her Better Belly Project 2.0.

The intestinal biopsy has been considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing celiac disease for a long time. But is this still true?

On October 1st, 2013 on the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) web site, opposing views were presented on whether an intestinal biopsy is always required for a celiac disease diagnosis.

Alessio Fasano, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist and director of the Center for Celiac Research at the Massachusetts General Hospital for Children, wrote an article titled, "A Biopsy Should Not Be Required to Make the Diagnosis." (1)

Peter H.R. Green, MD, from the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, explained his opposing view in an article titled, "A Biopsy Should Be Required to Make the Diagnosis." (2)

Alessio Fasano, MD

Alessio Fasano, MD Peter H.R. Green, MD

Peter H.R. Green, MDI seriously doubt that consensus among gastroenterologists, both in the United States and around the world, will be reached anytime soon. In this article, I attempt to summarize the opposing views on this important topic, beginning with the typical criteria for diagnosing celiac disease.

I conclude with my opinions on this controversial issue—not as a medical professional but as a gluten-sensitive person who has had a celiac disease endoscopy twice, with multiple biopsies taken from my duodenum each time.

All of my biopsies were negative for celiac disease, but I had been gluten free for over five years for the first endoscopy and for over seven years for the second endoscopy.

Criteria Typically Required for Confirming a Celiac Disease Diagnosis

As Dr. Fasano describes in his 2014 book Gluten Freedom, the following five criteria are typically required for a confirmed diagnosis of celiac disease:

- Signs and symptoms compatible with celiac disease – For more information, see What Are the Celiac Disease Signs and Symptoms?.

- Sufficiently high levels of celiac antibodies – For more information, see What Is the Best Screening Blood Test for Celiac Disease? and What Is the Celiac Disease Panel?.

- A genetic predisposition for celiac disease (having the HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8 celiac gene) – For more information, see What Is the Celiac Gene?.

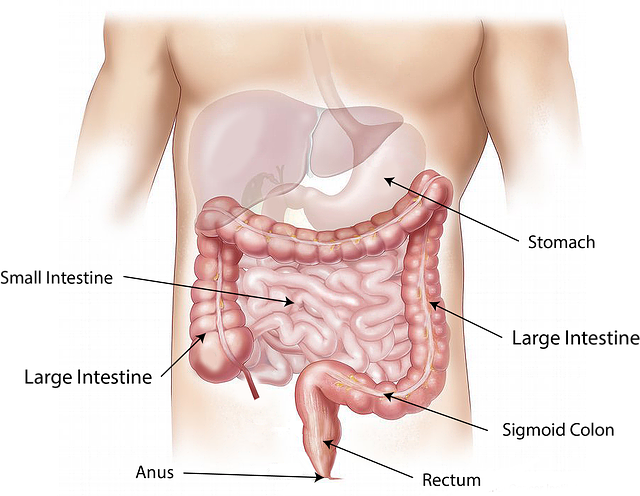

- Intestinal damage consistent with celiac disease, which is detected by an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, which some people refer to as a “celiac disease endoscopy” – In addition to this page, see Celiac Disease Testing: The Small Intestinal Biopsy.

- Symptom resolution and normalization of blood testing following the implementation of a gluten-free diet – For information about the gluten-free diet, see the Gluten-Free Diet FAQ and the List of Gluten-Free Foods.

Dr. Catassi and Dr. Fasano's “Four out of Five Rule” for Diagnosing Celiac Disease

While the vast majority of people with celiac disease will fulfill all five diagnostic criteria listed above, there are still exceptions for each of the five clinical pillars to justify what Dr. Catassi and I suggested as the most rational approach to diagnose celiac disease. If indeed, our suggestions are followed, four of the five criteria should be sufficient to cover all people affected by celiac disease.

— Alessio Fasano, MD, author of Gluten Freedom

In a 2010 paper published in the American Journal of Medicine, Carlo Catassi, MD, MPH, and Alessio Fasano, MD, introduced the “four out of five rule.” If any four of the five criteria for a celiac disease diagnosis are met, then the 5th criteria can be omitted in diagnosing the disease. (3)

One major implication of this recommended “four out of five rule” is that in selected cases, the typically required intestinal biopsy can be excluded from the diagnostic process.

As Dr. Fasano argues in his 2013 AGA article about how the intestinal biopsy should not be required in all cases, “In many cases, all five clinical, serological, and histological criteria are consistent and the diagnosis of celiac disease is straightforward.”

However, he points out, major limitations of the small intestinal biopsy have become clear over time.

For example, if the biopsy specimen from the small intestine is not cut correctly, normal tissue might appear to be deteriorating. In addition, celiac disease lesions can be patchy, meaning that some areas in the small intestine appear normal while other areas have varying degrees of damage.

“What also became clear over time,” Dr. Fasano states, “was the evidence that when celiac autoantibodies [tTG-IgA and EMA-IgA] are found at high titers in a patient with typical symptoms, the probability of identifying a celiac enteropathy at the small intestinal biopsy is practically 100 percent. In these cases, the intestinal biopsy does not add any relevant information for celiac disease diagnosis and treatment.”

In Dr. Fasano's expert opinion, the intestinal biopsy is no longer the “gold standard” for diagnosing celiac disease. He says, “In fact, it is not the silver standard, nor even the copper standard! One main reason is that someone with celiac disease may have no damage to the small intestine. Not yet.” (4)

Some Gastroenterological Associations Have Developed New Guidelines That Allow Diagnosing Celiac Disease Without an Intestinal Biopsy—In Some Cases

In 2012, the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) as well as the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) adopted this recommendation to diagnose celiac disease without biopsies in selected children and adolescents.

However, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) still require the small intestinal biopsy to confirm a celiac disease diagnosis.

If you're interested in diving into the exquisitely detailed diagnostic guidelines of the AGA and the ACG for celiac disease, see the following:

- AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease

- ACG Clinical Guidelines: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease

“Borderline” Situations Where Patients Don't Meet All Five Criteria for a Celiac Diagnosis

In his 2013 AGA article, Dr. Fasano describes the following “borderline” situations that cause both children and adults with celiac disease to fall through the cracks because they don't meet all five diagnostic criteria:

- Some people have no (or minimal) symptoms consistent with celiac disease, but they meet all the other criteria for diagnosis. This is often referred to as asymptomatic celiac disease. Such people are typically identified during routine screening, which is performed because they have a family member diagnosed with celiac disease.

- Some people have positive blood tests for celiac disease, but there are no histologic findings in their duodenum biopsies that are characteristic of this disease (or the biopsies show “nearly” normal tissue). This is called potential celiac disease.

- Some people have negative serology for celiac disease (lacking both tTG and EMA antibodies), although they meet all of the other criteria for the disease. This is called seronegative celiac disease.

- Rarely, people with celiac disease lack the celiac gene (HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8). This occurs is .4% of celiac patients.

- Despite following a gluten-free diet, some people continue to have symptoms for a long time.

By applying Dr. Fasano's “four out of five rule,” these people would no longer fall through the cracks. The first four groups of people would be diagnosed with celiac disease and placed on a gluten-free diet to treat symptoms (if they are present) and to prevent late-onset complications.

The last group, consisting of people with celiac disease who continue to have symptoms despite following a gluten-free diet, require additional medical and/or nutritional help. The following are some of the possible causes of their continuing symptoms:

- They are inadvertently consuming unsuspected sources of gluten or hidden gluten.

- They might have a co-existing condition such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or food sensitivities.

- Some other condition might be causing their villous atrophy. These other conditions must be ruled out or treated accordingly. They include SIBO, Crohn's disease, food allergy, and infectious enteritis (which is an infection, usually caused by bacteria or a virus, that causes inflammation of the small intestine).

- They might have refractory celiac disease, an uncommon yet typically more serious form of the disease. Symptoms are often severe and require therapeutic interventions beyond the gluten-free diet. (5)

Dr. Green's Case for Requiring a Positive Intestinal Biopsy to Make a Celiac Disease Diagnosis

It is a great error to misdiagnose celiac disease resulting in an unnecessary lifelong gluten-free diet. The knowledge of celiac disease is not great among primary care physicians, and the opportunity for misinterpretation of the very strict new ESPGHAN guidelines is great.

— Peter H.R. Green, MD, "A Biopsy Should Be Required to Make the Diagnosis"

The preceding quotation from Dr. Green summarizes his arguments for requiring an endoscopy procedure to confirm villous atrophy before making a celiac disease diagnosis. Here are some of the details, but read his relatively brief paper if you are seeking to fully understand his position.

- The Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, where Dr. Green works, is increasingly encountering patients who have been diagnosed with celiac disease based on “minor elevations of tissue transglutaminase IgA antibody levels, genetic testing alone, stool or saliva tests, or even isolated tissue transglutaminase IgG or anti-gliadin antibody levels.”

- The gluten-free diet, as a treatment for celiac disease, is expensive and lifelong. The lifestyle imposed by following this diet can be socially isolating and affect a patient's quality of life, including his or her ability to eat out and travel.

Dr. Green states that because “the personal and financial burden of a false diagnosis of celiac disease can be great,” the diagnosis of celiac disease must be “well founded.” - Taking multiple biopsies, including from the duodenal bulb, can offset the problems with the small intestinal biopsy and “increase the diagnostic yield.”

- If a person doesn't have villous atrophy, he or she doesn't need to begin a gluten-free diet.

- Some children and adults experience “temporary celiac or gluten autoimmunity.” In such patients, celiac antibodies diminish even though these patients continue eating gluten. Biopsies are normal, and subsequent blood tests for celiac disease are negative.

Dr. Green states that these patients might receive “a label of potential or latent celiac disease,” but they can eat gluten. However, he admits, they must be closely monitored for celiac disease. - Dr. Green believes that pediatricians will apply the “no-biopsy-necessary” policy to diagnose celiac disease without strictly following the ESPGHAN guidelines.

- Biopsies are necessary not only for diagnosis but also for prognosis. He states that persistent villous atrophy that is detected in follow-up biopsies is associated with an increased risk of a type of cancer called lymphoma. To investigate this possibility, an initial biopsy must be performed to obtain the celiac disease diagnosis.

My Opinions About the Intestinal Biopsy Requirement for a Celiac Diagnosis

I support Dr. Fasano's “four out of five rule.” It makes the most sense to me, given the state of today's advanced testing methods for celiac disease and given all those people who now fall through the cracks and don't receive the diagnosis of celiac disease when—I agree with Dr. Fasano—they should.

Of course, patients should not be diagnosed with celiac disease without their doctor following sanctioned guidelines for diagnosing the disease. Granted, no single set of guidelines is sanctioned by all gastroenterological associations. However, the justifications for the diagnosis of celiac disease that Dr. Green reports are obviously insufficient.

However, I believe that people with asymptomatic celiac disease, potential celiac disease, or seronegative celiac disease should be placed on a gluten-free diet, if they are willing, of course. Why wait until the disease progresses to the point of causing more damage to the small intestine and/or serious complications such as osteoporosis, peripheral neuropathy, or lymphoma?

Why not prevent worse things from happening?

Celiac disease doesn't appear overnight. It takes a while for any autoimmune disease to develop, sometimes decades. Why wait until the disease has reached a level of severity that would cause more suffering and maybe even a shorter lifespan? Why not catch celiac disease in its earlier stages?

According to Umberto Volta, MD, “It has been shown that both IgA anti-endomysial [EMA-IgA] and high-titre tissue transglutaminase antibodies [tTG-IgA] are closely related to gluten-dependent flat mucosa.” (6)

In other words, by the time patients have high titres (concentrations) of celiac antibodies, they most likely have flat mucosa (that is, total villous atrophy). At this point, their celiac disease has reached an advanced stage.

So if patients have signs and symptoms compatible with celiac disease, high concentrations of celiac autoantibodies, the celiac gene, and they respond well to the gluten-free diet, why make them undergo the small intestinal biopsy to confirm what is already obvious?

Furthermore, regarding patients who are diagnosed with celiac disease without an intestinal biopsy (but they meet the other four criteria): If they are still experiencing symptoms after adopting a gluten-free diet, it certainly might be worth their while to undergo an upper GI endoscopy (and perhaps even a colonoscopy) as part of additional diagnostic testing.

Dr. Fasano makes a strong case for his “four out of five rule” in his AGA article. However, for vastly more details that support this approach to diagnosing celiac disease, read his book Gluten Freedom. If you're on the fence and you read this book, you might just decide that Dr. Fasano's side of the fence sports the greener grass and is the best place to sit.

In 2012, a gastroenterologist who specializes in celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity told me that my two copies of the HLA-DQ2 celiac gene puts me at the highest risk for celiac disease. He said that celiacs with this genotype tend to be the sickest of all celiac disease patients and the most sensitive to tiny amounts of inadvertent gluten exposure.

Even though I went gluten free in 2006 before getting tested for celiac disease (due to my and my doctors' lack of knowledge), I have no regrets about going gluten free when I did.

At that time, perhaps I would have fulfilled all five diagnostic criteria for celiac disease, including having a positive intestinal biopsy. Or perhaps I was in the early stages of celiac disease and I prevented worse things from happening by going gluten free. And I've been in remission ever since…

Or perhaps my body was teetering on the brink of developing celiac disease, and I prevented this disease by going gluten free.

I'll never know because I'll never do a gluten challenge. Why risk becoming really sick? No one could guarantee I'd recover from that gluten challenge and return to my current state of health (even though it's not yet where I want it to be).

My bottom line is: My body did not respond well to gluten. Giving up gluten was one of the best things I have ever done for my health.

That said, I do wish I had been tested for celiac disease before going gluten free. That's my one regret.

References

If you're interested in delving deeper into whether the intestinal biopsy should be required in all cases to confirm a celiac disease diagnosis, check out Further Reading About the Intestinal Biopsy for Diagnosing Celiac Disease Diagnosis.

1. Fasano, A. A biopsy should not be required to make the diagnosis. American Gastroenterological Association web site. Oct 1, 2013.

2. Green, HR. A biopsy should be required to make the diagnosis. American Gastroenterological Association web site. Oct 1, 2013.

3. Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease diagnosis: simple rules are better than complicated algorithms. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):691-693. [PDF]

4. Veltman E. Dr. Fasano on new gut & autoimmune research, autism, & clearing up the gluten confusion with his new book. The Tender Foodie Blog. May 1, 2014. [Blog Post]

5. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray, JA. Classification and Management of Refractory Celiac Disease. Gut. 2010;59(4):547-557. [PDF]

6. Volta U. Coeliac disease: time for a new diagnostic approach in symptomatic children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(3):241. [Full Text]

CeliacFAQ.com home page > Celiac Disease FAQ > Is the Intestinal Biopsy for Diagnosing Celiac Disease Always Necessary?